CONTENTS

- 0. Introduction

- Chapter 1: PERSON

- Chapter 2: LIFE

- Chapter 3: ENVIRONMENT

- Chapter 4: SOCIETY

- Chapter 5: CULTURE

- Chapter 6: COMMUNICATION

- Chapter 7: ACTIVITY SYSTEM

- Chapter 8: THE COGNITION SYSTEM

- Chapter 9: EDUCATION

- Chapter 10: WORK

- Chapter 11: MANAGEMENT

- Chapter 12: COOPERATION

- Chapter 13: CONCERNS

- Conclusion

CHAPTER 8: THE COGNITION SYSTEM

The formation of the human cognition system begins even before birth.

There are many cognition ways.

8.0. GENERAL CONCEPTS

The theory of cognition [1] is a branch of philosophy (Greek: gnoseology), a holistic doctrine of the human and their environment.

Self-regulating systems function, change, develop, and degrade — are born and die — according to objective laws and their legal manifestations. It is interesting and fascinating to reveal the connections and dependencies that can serve as a basis, cause, prerequisite, or obstacle to various phenomena or processes. Laws and patterns should be revealed, studied, and considered, if only because they operate everywhere, regardless of people’s wishes and will. A person can slow down, speed up, direct, and also destroy self-regulating processes a little, but they cannot develop someone or something.

The theory of cognition covers:

- the possibility of cognition;

- the relationship of cognition to reality;

- sources, principles, and methods of cognition.

In the previous chapter, we outlined in general the activity system; in this chapter, we will proceed to consider the cognition system.

The same laws apply to the cognition system as those we have discussed in relation to the activity system. This means that each element of the cognition system to some extent contains all the other elements of this system.

[1] Those who wish to study the theory of cognition more deeply should familiarize themselves with the doctrine of structure and function, the doctrine of development, dialectics , as well as trialectics (see Figure 2.11.2.).

8.1. WAYS OF COGNITION

We will begin our consideration of the cognition system with ordinary cognition, which a person acquires along with their native language. However, other types of cognition also play a significant role: artistic, religious, philosophical, scientific, and intuitive cognition. Each type of cognition corresponds to its own way of formation.

Each of the ways of cognition makes it possible to discern and understand matters, phenomena, and processes that cannot be revealed in other ways.

Philosophical cognition gives us an idea of development; religious cognition gives us an idea of eternity; artistic cognition gives us an idea of beauty. All of these concepts would be impossible to discuss, for example, within the framework of scientific cognition. If you ignore or fail to understand any of the ways of cognition, it will be impossible to reach a satisfactory level on the others, and understanding becomes highly unlike.

The dominants of the cognition system may change throughout life, but all of its elements are continuously functioning. For example, a newborn does not yet philosophize, but from a certain point the child begins to think, to find connections, to draw logical conclusions, to see causes and consequences, to notice prerequisites.

The cognition system begins to form even before a child is born. As has been said more than once in this book, in the first year of life, concepts begin to form such as “I” and “we”, “mine”, “cannot”, “must” (see 5.2.). The formation of an adequate “I” is a prerequisite for the formation of “we” (family, community). “We” is a prerequisite for loyalty, belonging to a group, the emergence of national consciousness and a different identity.

Ordinary cognition emerges with the acquisition of the native language, in which a person learns to feel themself and the world around them. In this regard, they learn what things are called, how they affect each other, and how they relate to each other.

Artistic cognition awakens the ability to grasp harmony and beauty, rhythm and tension, color and form, etc.

Religious cognition is accompanied by the ability to see the universe and eternal connections, something that the rational consciousness cannot grasp.

Intuitive cognition occurs without the involvement of the senses: that is, directly, naturally, at the call of the heart. Intuitive cognition and behavior are influenced by the super- and subconscious.

Philosophical cognition attracts those who wish to comprehend the truth. It consists of detecting, ordering, and using the basic principles of thinking. In philosophical interpretation, thoughts are constructed that make it possible to look deep into the thoughts already voiced, to distinguish and connect the essence and appearance; the general, specific, and individual; movement and rest; the whole, its parts, subsystems, and elements.

Scientific cognition is characterized by the ability to formulate problems and clearly reasoned connections between causes, results, and consequences; the ability to consider, measure, assess, and describe; the ability to consider any matters, phenomena, and processes systematically and comprehensively.

8.2. SCIENTIFIC COGNITION

Later in the book, we will focus on scientific cognition and will not examine in detail other types. Everyone who aspires to be a citizen needs to master the art of formulating problems, establishing facts, making proposals, and giving recommendations based on research results.

- Every citizen should have the ability to see a problem and to find the reasons for its occurrence and existence.

- If the system of causes cannot be detected with the naked eye, and it is dangerous to continue on the wrong path, then research should be conducted.

It sounds paradoxical, but the main consumer of the results of a research study are research studies themselves. Under favorable conditions, it takes 5-7 years to form a workable research center. Research begins with detecting a system of causal and functional connections formed in or between any system. Simply put, researchers begin to search for an answer to the question “why is this?”

A research study is preceded by descriptions, previous studies, questionnaires, and everything else that contributes to detecting connections and dependencies.

BASIC POSTULATES

Reality is only describable. Problems can be researched.

Research could also be carried out by means of a hypothesis (a scientifically grounded assumption).

A hypothesis should be tested (not proven!).

SUBJECT AND OBJECT OF RESEARCH

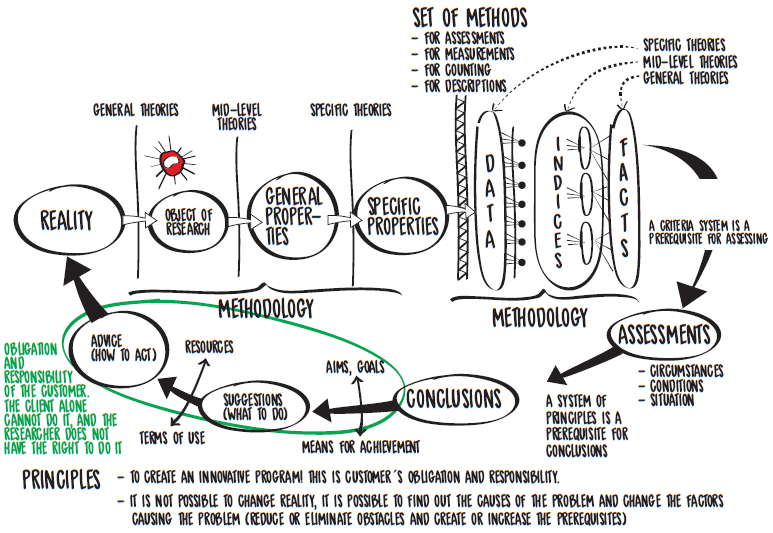

The object of research is a problem (see Figure 0.3.3.), and the matter of research is everything that characterizes the problem — everything that is measured, assessed, counted, or described in the research.

The scientist is responsible for the possible consequences of using the results of research!

The subject of research is the person or set of persons vested with decision-making authority at all stages of the research and responsible for the correct execution of academic requirements. The subject of research is responsible for the reliability, sufficient consistency, and timeliness of the raw data, their accurate processing, and that the facts are based on gathered data. The subject is also responsible for the people and environment involved in the research. In addition, any scientist (whether they are a subject or just a participant in the research) is responsible for the possible consequences of using the results of that research!

RESEARCH PREREQUISITES

There are a number of prerequisites for organizing research, including academic freedom and independence.

Research needs a theoretical framework (general and intermediate level theories, and specific theories — see 8.3.), a system of principles, and methods for collecting and processing raw data, and analyzing and summarizing them.

- A questionnaire is not research, it is just a method of collecting baseline data!

- Through a questionnaire, it is possible to collect opinions that characterize for the most part the respondents themselves, and not the matter of discussion.

In most cases, research ends with the establishment of scientific facts. However, it happens quite often that there is a substitution, and instead of research, a survey is conducted or a description is prepared based on assessments and opinions.

It is worth repeating once again that descriptions are needed only to formulate the problem. A questionnaire is not research, it is just a method of collecting baseline data! Through a questionnaire, it is possible to collect opinions that characterize for the most part the respondents themselves, and not the matter of discussion. Of course, it cannot be ruled out that a respondent will be an expert whose words will contain the answer to the question posed. However, in general, the researcher does not have the opportunity to separate the opinions of professionals from the opinions of dilettantes and the profane (see 1.7.). Based on anonymous responses, only the structure of respondents can be ascertained.

In order for the facts established in the research to have practical value, they must be linked to the next level of theories, because the meaning of the facts is formed in context.

In order for the facts established in the research to have practical value, they must be linked to the theories of the next, higher level, because the meaning of the facts is formed in context. To assess the facts, it is first necessary to crewell as before each stage begins, including before formulating proposals for the further use of established facts.

Such proposals presuppose the availability of means, resources, and conditions for their application. It is also necessary to define the principles of further activity and the criteria for assessing both the activity itself and its results.

Only after that is it possible to plan innovative processes (see 11.3.), based on the results of the research.

The results of a research study are, of course, of much broader significance than the improvement of the practice from which the problem was drawn. Based on the results of a research study, it is possible to conduct much more in-depth and detailed research; the results of a research study enable improving the educational process, writing articles and monographs, and communicating with other researchers.

According to a rule common in the scientific community, it should be possible to verify the results of any research. In society and culture, things can change very quickly, and all factors cannot be kept in place for a long time.

Science has no goals. People can have goals. People try with the help of research studies to acquire new, cognitively and practically significant knowledge, as well as to find opportunities to apply it. The activity of scientists is, among other things, in processing and preserving the knowledge gained and assessing its validity. It is the duty of scientists to improve terminology and preserve the native language among the cultural languages.

- The duty of a scientist, among other things, is to improve terminology and preserve the native language among the cultural languages.

- No excuse can justify a careless attitude toward language!

STEP-BY-STEP RESEARCH

A full-scale (ideal) empirical study in the field of social science (see Figure 8.2.1.) should include at least the following steps (for clarity, what the subject of the research needs at each step is added):

- Formulating an empirically known contradiction as a problem. For this, the subject of the research needs a methodology and a general theory.

- Defining the boundaries of the matter of the research. The matter of the research is everything that characterizes the object of research and that is measured, assessed, counted, and described within the framework of this research.

- Formulating the general properties of the problem. This requires a methodology and intermediate-level theories.

- Reducing the general properties to the operational level; detecting specific properties. This requires a methodology and specific theories.

- Measuring, assessing, counting — fixing the data regarding all the specific properties. This requires a set of methods for collecting baseline data.

- Logical, statistical, or mathematical data processing. This requires a method for data processing.

- Compiling indices (see 6.0.) relative to all common properties. Again, this requires specific theories and a methodology.

- Deriving specific scientific facts from indices. This again requires a methodology and intermediate-level theories.

- Detecting general scientific facts. Again, a methodology and general theory are needed.

- Summarizing, reporting, making predictions and scenarios for the near and distant future; possibly writing articles, monographs, and academic research reports; updating lectures and courses, etc.

If it is found that the new knowledge that has been discovered requires the creation of a system of measures to reduce (or eliminate) the causes of the problems, as well as the formulation of global, fundamentally important conclusions, proposals, and recommendations, then it should be kept in mind that there is at least half of the work ahead.

- Assessing the facts detected in the course of the research (the causes of the contradictions that constitute the problem). This requires a system of criteria.

- Conclusions about the practice that has existed so far and its factors. This requires a system of principles.

- Formulating the aim and goals. This task cannot be accomplished by the researchers themselves. Setting and refining the aim and goals are decisions accompanied by responsibility for further activity; therefore, it is the prerogative (non-delegable right) of a public authority or whoever else commissioned the research.

- Formulating proposals and advice on achieving goals. For the most part, this task is also beyond the power (and cannot be allowed) of researchers. Instead of proposals, researchers can show those who commissioned the research (the client) alternatives and explain what goes along with the possible choice. The preferred option should be determined by the client themself, they are responsible for further activity. To do this, the research subject should help the client to reach a level at which they would be able to understand not only the individual factors of the problem, but also the whole system of these factors. Also, the client should consider how the processes (regulatory mechanisms), which launched as a result of a particular decision, operate at various levels, and, when making a decision, anticipate the results and consequences.

Experience shows that, for the most part, neither the so-called practitioners who commissioned the research nor the researchers themselves are capable of interpreting the results on their own. Researchers can make predictions and scenarios based on the results of the research, but the clients do not understand what the researchers have described and are unable to comprehend the entire system without proper training.

- Researchers should not (do not have the right to) make proposals or give advice.

- Researchers can inform practitioners so they are able to prepare reasonable decisions. (For bad decisions, see Figure 11.2.3.)

- What, when, and how to do it or what to avoid should be decided by the one who is responsible for executing the decision and the accompanying results and consequences.

However, little would come from so-called translators who could help the clients to understand the researchers. At one time, the sociological laboratory of Tartu State University signed a research contract only if those commissioning the research accepted the obligation to participate in all its stages, at least to the extent of being aware of what steps were being taken and why this particular activity was being undertaken. In addition to so-called supervision, the client should have organized a seminar for senior managers. The seminar examined those phenomena and processes within which the contradictions had become so serious that they led to the emergence of a contract to identify their causes. It should be noted that these measures have proved effective.

- Drafting a program of innovations (see 11.3.).

- Advising the client about innovations. Participating in simulation exercises and seminars organized by the client (see. 11.4.).

- A conference that involves both the researchers and the client, as well as invited guests dealing with similar issues.

It is not reasonable to divide research studies, and especially social science studies, into fundamental (i.e., primary) and applicable (secondary) research, because the main reason for conducting any studies is their necessity. The results of the study can be used in subsequent studies. They can be relied upon when detecting new problems; improving theory, methodology, and methods; maintaining or changing practice; as well as in studies, linguistics, etc.

SOCIAL SCIENCE STUDIES ARE COMPLEX

There are a large number of questions in scientific cognition that do not exist in the natural and exact sciences, because humans are infinitely complex and there is nothing in society that can be considered permanent. People are both members of society and representatives of culture, and at the same time, they are representatives and members of the community as well as their family. There are also institutions, businesses, organizations, and informal associations that influence people in their own way.

Gathering enough reliable data and then detecting reliable statistical and scientific facts in social science studies is at least as difficult as in any other field.

Unfortunately, knowledge about society is poorly disseminated. Citizens should consider how to organize everything so that knowledge is not replaced by opinion, belief, rumor, or description, and so they avoid a careless attitude (they say that it’s okay, others don’t have even that).

One of the signs of the quality of social science research is that researchers have theories, methodologies, and methods (both for collecting and processing reliable data and for elevating the data into statistical and scientific facts), which they are prepared to present to the public. If the prerequisites of research remain hidden, there is a high probability that we are dealing with unreliable research. Unfortunately, the same can be said in the case when clients do not bother (due to laziness or inability) to participate in the research at least enough to clarify for themselves the meanings of the concepts.

SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION, RESPONSIBILITY, AND CITIZENS

Qualitative sociological research can be useful to society only if citizens have the training to see the problems and understand the measures taken regarding the problems and their causes. If citizens do not have training in the field of society and culture, then social control will not be satisfactory, and society may stagnate.

Research in the field of society and culture is necessary in cases where those responsible for decisions will really have to (rather than pretend to) be personally responsible for their activity and the possible consequences. Practice shows that the so-called bosses who do not need to be personally responsible for the consequences of their activity (or inactivity) do not commission any research because they do not need actual knowledge. In such cases, knowledge does not differ from opinions, beliefs, dreams, and intentions. Where society exists without goal visualization and feedback, sociological research is not conducted; it can be assumed that such countries cannot stay on par with rapidly developing states.

Practice shows that research is commissioned by bosses who feel personal responsibility for the results and consequences of their activity (as well as inactivity).

The need for scientific information arises in those who:

- distinguish between knowledge, opinions, dreams, etc;

- know what is fact, infonoise, and demagoguery;

- know what can and should be measured, assessed, counted, and described so that the data obtained are reliable;

- understand the cognition system; know the possibilities and limits of scientific knowledge, as well as its connections with other ways of cognition;

- understand the activity system; know the interrelationships of the elements of the activity system, including certain (deterministic) connections under the circumstances;

- understand that social action requires both administrative (formal, stemming from social connections) and moral (informal, stemming from cultural connections) rights, and that the use of rights comes with an obligation to be responsible for everything that begins to occur as a consequence of that activity in the future; distinguish between essence and appearance;

- be able to and be interested in thinking systematically, distinguishing and linking the functioning, change, and development of systems.

Scientific research studies, as well as their value, significance, and role are best understood by those who themselves have participated in a particular study. The same is true of other ways of cognition. For example, people who have not participated in the creative process find it difficult to understand creativity and creative individuals.

The notion that applicable research is simpler than basic or fundamental re- search and that it does not require a correct theoretical, methodological, and methodical framework is incorrect and misleading.

Sadly, world history is full of examples of management taking scientists and science seriously only in a crisis that could destroy everything, or when a country is on the brink of war, when for victory, it is necessary to be many times stronger than the enemy.

WHY DO WE NEED SCIENCE?

Society, first and foremost, needs a scientific way of thinking and an understanding of the role of scientific research in the cognition system, the prerequisites of scientific research, and the value of the knowledge detected in the course of research.

It has long been known that the profane and dilettantes hate science and scientists alike. Those who get into high positions of management (and can thus prohibit or order) by dishonest means often sneer at science and scientists, trying to use this practice to justify their arrogance. Experience has shown that it is impossible to achieve anything worthy and sustainable in an unworthy way.

Science is needed in order to:

- see a little forward and take at least a few steps in a preconceived direction;

- provide goal visualization and feedback to processes, the flow of which in the right (appropriate) direction is important to the subject;

- through scientific research studies, discover the reasons for successes and failures;

- reveal, translate, transmit, disseminate, and consider knowledge gained in other countries, both strategically and in our daily activities;

- form a scientific way of thinking, because science presupposes the education, awareness, and experience not only of scientists, but also of others;

- pave the way for amazing discoveries, finding new things, getting rid of the old.

In addition,

- Science protects against deceivers and deception.

- Science helps cleanse thought constructs of outdated ideas, rid ideological constructs of fraud and organizational structures of unjustified authority and people accidentally caught up in them.

- Science gives freedom to find new solutions and more effectively preserve everything that needs to be protected.

Science by itself does nothing — people do. Thanks to the results of scientific research and scientific thinking, thanks to orientation in the cognition system, people can act more expediently.

Social sciences are necessary and make sense if constitutional institutions are obliged to report regularly to citizens on their activity and its results.

A state can be considered knowledge-based if those who make decisions and those who execute them understand the need to take responsibility for their activity and its consequences.

Social sciences are necessary, make sense, and do not become dangerous (not alienated to the people) if constitutional institutions are obliged to regularly report to citizens on their activity and its results (report on the circumstances, conditions, and situation of the society and the state). Such a report should not take the form of an official message, but rather a public social debate.

Taking the results of research into account and using them involves not only scientists, but also civil society as a whole. For this, every citizen needs training in cognition, the right to be informed, and the opportunity to become closely acquainted (gain personal experience) with the activity of state and municipal government agencies. Without the unity of educatedness, informedness, and experience, residents cannot become citizens and bearers of supreme power.

8.3. METHODOLOGY AND METHODS

In Estonia, it is sometimes accepted to think of methodology as the set of methods. In our interpretation, methodology is a philosophical doctrine of principles, the observance of which underlies the processes that accompany the entire system of human activity (see also Figure 0.3.2.).

At Estonian universities, theory and methods are considered more or less carefully in the research defended by bachelor, master’s, and doctoral students, while the basics of methodology, in most cases, are not taken into account at all.

In scientific research, the necessary system of principles should be created and used to:

- detect the object and the matter;

- be able to look “behind” the results of the study;

- think of connections and dependencies, to identify their meanings;

- expand the application of the research results.

There are at least three kinds of principles:

- principles arising from cultural and social connections (e.g., the principle of humanity, the principle of the continuity of culture, the principle of the protection of the living environment, etc.);

- principles necessary to consider the object of attention (e.g., the principle of multiple points of view, including, necessarily, the principle of separate and joint consideration of statics and dynamics);

- principles of the organization of learning (didactics; e.g., from distant to close, from familiar to unfamiliar, from simple to complex, etc.).

Methodology is a necessary, but by no means sufficient prerequisite for obtaining a clear picture in a professional activity, and achieving reliable results and assessments.

Methodology is a philosophical doctrine of principles that must be known and taken into account in order to navigate in various spheres of life, find solutions, engage in activities, and predict, discover, and assess the results and consequences that go along with all of this.

In this book, we only mention the principles that must be taken into account when conducting scientific research that is considered satisfactory in the field of society and culture. Note that to understand some (any) system (matter, phenomenon, or process) it is necessary to be able to describe its characteristics as fully as possible and subsequently consider them both separately (separate consideration) and connected with each other (joint consideration).

- The principle of multiple points of view; (see Figure 0.3.1.);

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of dynamics and statics (processes, phenomena, and matters) (see Figures 0.3.3. and 0.3.4.);

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of self-regulation and goal-oriented influences (management, governance, administration, possession, formation of connections, etc.) (see Figure 2.9.1.);

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of levels of regulation and management (see Figure 7.2.1.);

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of social and cultural connections;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of the past, present, and future;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of expediency, efficiency, and intensity;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of the tangible (matter), intangible, and virtual environment (see Figure 3.0.1.);

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of circumstances, conditions, and situations;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of essence and appearance;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of systematicity and complexity (see Figure 2.11.0.);

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of the general, specific, and individual;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of main, auxiliary, coercive, additional, parallel, etc. processes;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of functioning, change, and development;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of the aim, goals, and means;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of rights, obligations, and responsibilities;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of energy, rhythm, and tension;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of the subjective and objective;

- The principle of separate and joint consideration of fundamental and applied problems.

METHOD AND SETS OF METHODS

It is only possible to measure quantities using well-known techniques (measuring, etc., see also 1.0.). In the case of humanities and sociological research, the researcher should collect data mostly concerning qualitative attributes, and therefore, as a rule, the researcher themself creates methods for collecting baseline data. Through oral and written questionnaires, observations, experiments, etc., it is possible to collect only “fragments” of what needs to be known for research. In the first stage of analysis, these “fragments” should be combined into indices (see 6.0.).

- A method is a way to stay the course, achieve goals, and fulfill obligations and tasks. A method serves as a tool for any professional activity.

- A set of methods describes different methods used in any activity.

An analysis of the second level is based on the indices that characterize the general properties of the object of research. In the case of humanities and social science research, the techniques of collecting raw data are so imprecise that for every detail about which knowledge or opinions are needed, data must be collected using at least two fundamentally different methods.

A method is of great value. Mastering methods can be considered a measure of skill. Unfortunately, methods are also widely used today in Estonia by which the data collected can only be interpreted using additional methods.

For example, as noted above, in the case of formalized questionnaires and/or interviews, no one can know for certain whether the data collected relate directly to the question posed, or whether they convey the outlook, system of dispositions, mood, attitudes of the respondent, etc. In this case, it would be necessary to conduct an additional experiment, observation, or analysis of diaries in order to convert the available data into adequate information.

The researcher must ensure the reliability of the raw data and results. Based on this, novice researchers can be advised to create a strategy and set of methods for processing data even before the collection of primary data begins. It would also be useful to create an algorithm for compiling indices before the collection of primary data begins.